Hantavirus—a name that sounds like a footnote in a medical journal—has suddenly vaulted into public consciousness, following reports that it was the cause of death of Betsy Arakawa, the wife of legendary actor Gene Hackman. Despite this tragic high-profile case, the virus remains an enigma to many. Most people only know it as something linked to rodents. But what really is hantavirus? How does it spread? And more importantly—could it be quietly circulating in places closer to home than we think?

A team of researchers at Virginia Tech may have just pulled back the curtain on one of nature’s stealthiest pathogens. Their findings, recently published in Ecosphere, mark a pivotal step forward in understanding the virus’s ecology, behavior, and potential for outbreak in the U.S.—and possibly beyond.

A Virus Cloaked in Mystery

Hantaviruses are a family of zoonotic viruses—meaning they jump from animals to humans—and are carried asymptomatically by rodents. Unlike other diseases that require direct bites or scratches, hantavirus infects humans in a far more insidious way: through the air. People become exposed by inhaling microscopic particles of rodent excreta, urine, or saliva—often after sweeping dusty floors or cleaning out rarely used sheds and cabins.

While many people may shrug off symptoms resembling the flu or a cold, certain strains of hantavirus can cause Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome (HPS), a condition with a mortality rate of up to 40%. And that’s just in the Americas. In Asia and Europe, other strains like Hantaan and Dobrava-Belgrade viruses cause hemorrhagic fevers that attack the kidneys and internal organs. In other words, hantavirus isn’t just lurking in barns and attics—it’s a global health risk with pandemic potential.

Yet for all its deadly potential, the virus remains vastly under-studied. Until now.

Unlocking the Wild Code: Virginia Tech’s Breakthrough

To better understand where and how hantavirus circulates in the wild, the Virginia Tech team turned to a rich but underutilized resource: the National Ecological Observatory Network (NEON), a nationwide program funded by the National Science Foundation.

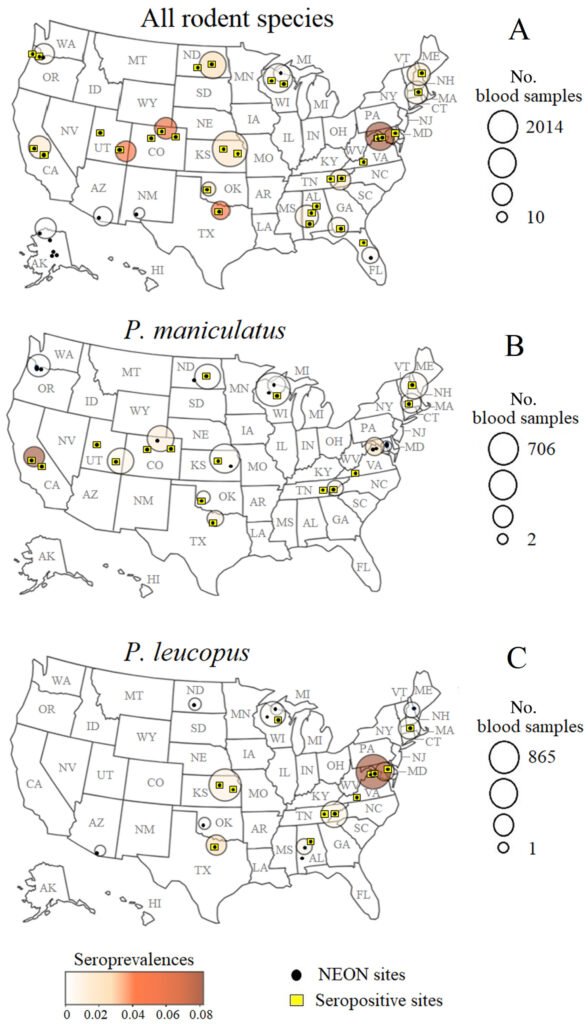

Over five years, NEON collected and analyzed 14,004 blood samples from 49 rodent species across 45 sites in the U.S., ranging from deserts to forests and grasslands. This treasure trove of ecological data allowed researchers to map the geographical spread of hantavirus like never before.

The results were eye-opening. The team pinpointed three major hotspots of hantavirus circulation in wildlife: Virginia, Colorado, and Texas—regions with very different climates and ecosystems. Even more strikingly, they identified 15 rodent species carrying the virus, six of which had never before been linked to hantavirus.

“This study fundamentally shifts our understanding of where hantavirus lives and who carries it,” said Paanwaris Paansri, a Ph.D. student in Virginia Tech’s Department of Fish and Wildlife Conservation and co-author of the study. “It’s not just the deer mouse anymore.”

Meet the Carriers: A Growing List of Suspects

The deer mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus) has long been public health enemy number one when it comes to hantavirus in North America. But the study reveals that the virus is much more promiscuous in its host selection than previously thought.

Some of the newly identified hosts live in areas where deer mice and white-footed mice (Peromyscus leucopus) are rare or even absent, hinting at a broader and more adaptable host range than previously believed. This could explain “mystery” cases of hantavirus in humans—illnesses in places where the usual rodent suspects don’t exist.

“This expands our understanding of the virus’s basic biology,” said Paansri. “It shows that the virus can adapt to different hosts in different environments. That has direct implications for public health surveillance and outbreak prediction.”

Climate Change: A Catalyst for Rodent Booms and Viral Doom

Beyond identifying new hosts, the researchers also studied seasonal trends and climatic influences. The findings support a worrying possibility: climate change may turbocharge hantavirus transmission.

Rodent populations tend to boom during warmer, wetter seasons. Increased precipitation leads to more food, which in turn leads to rodent population surges. But as the seasons dry out, the conditions shift: dry, dusty environments are ideal for aerosolizing rodent waste—the vehicle through which the virus infects humans.

“We’re starting to see that rodent demography and virus prevalence can be predicted months in advance, based on environmental factors,” Paansri explained. “That opens up possibilities for early warning systems.”

In essence, climate change may not just bring higher temperatures—it may bring higher risk of hantavirus outbreaks, especially in areas that previously didn’t register on the public health radar.

The Hidden Epidemic: Why You Haven’t Heard More

Despite its severity, hantavirus infections remain poorly tracked. Many human infections go unnoticed because symptoms mimic other illnesses like influenza or COVID-19. Some people may get infected but never develop symptoms. Others may die before a proper diagnosis is made.

“There’s likely a significant undercount of actual infections,” said Paansri. “We believe many people may be exposed without ever knowing it.”

This stealthy nature makes hantavirus particularly dangerous—it can circulate quietly in wildlife and silently infect humans until a severe case draws attention. By then, it may be too late.

What This Means for You

So, what can be done?

The study’s implications are twofold. First, it calls for more vigilant monitoring of rodent populations, especially in the newly identified hotspots. Second, it stresses the importance of educating the public about the risks of hantavirus exposure, especially for people living in or traveling to rural areas, hikers, campers, farmers, and homeowners cleaning out old buildings.

Basic precautions can go a long way:

- Ventilate closed spaces before cleaning.

- Avoid sweeping or vacuuming rodent-infested areas (which can stir up contaminated dust).

- Use disinfectants and wear gloves and masks when dealing with rodent droppings.

Meanwhile, researchers plan to expand their work by studying how climate variations influence both rodent behavior and hantavirus prevalence—a crucial next step in predicting future outbreaks.

“We believe this study provides a model that can be applied to other wildlife-borne diseases,” said Paansri. “As we’ve seen with COVID-19, understanding how pathogens circulate in wildlife is key to preventing the next pandemic.”

The Bigger Picture: A Warning and a Window

Hantavirus, once a fringe topic of virology, is now emerging as a disease of global significance, not just because of its mortality rate, but because of how little we understand it. The virus sits at the intersection of ecology, climate science, and human health—a reminder that in a changing world, even the smallest creatures can carry the biggest threats.

The Virginia Tech study doesn’t just fill gaps in scientific knowledge—it redraws the entire map of hantavirus risk in North America. And as climate change and human expansion bring us ever closer to wildlife, it’s clear that silent pathogens like hantavirus won’t stay in the shadows forever.

As with all zoonotic diseases, knowledge is our first line of defense. And thanks to this groundbreaking study, we are now one step closer to anticipating, preparing for, and hopefully preventing the next deadly outbreak.

Reference: Francisca Astorga et al, Hantavirus in rodents in the United States: Temporal and spatial trends and report of new hosts, Ecosphere (2025). DOI: 10.1002/ecs2.70209