Beneath the waves of the Taiwan Strait, a long-lost piece of our evolutionary puzzle has resurfaced—by accident. A weathered partial jawbone, dredged from the seafloor by a fishing operation and later discovered in an antique shop, is now captivating scientists around the world. This ancient relic, it turns out, may have belonged to a Denisovan—one of humanity’s most elusive and enigmatic relatives. The discovery, reported in the journal Science, marks a thrilling expansion in our understanding of where Denisovans once roamed—and how their mysterious legacy lives on within us.

A Jawbone’s Oceanic Odyssey

The fossil in question was pulled from the depths of the Penghu Channel, a submerged corridor separating Taiwan from the Chinese mainland. Originally fated for obscurity, the jawbone passed through the hands of antique dealers until, in 2008, a discerning collector recognized its potential significance and donated it to Taiwan’s National Museum of Natural Science. There, it waited silently for years, its identity shrouded in ancient mystery.

What makes this fragment so extraordinary is not just its journey from ocean floor to museum shelf—but what it might reveal about a long-lost branch of the human family tree.

Who Were the Denisovans?

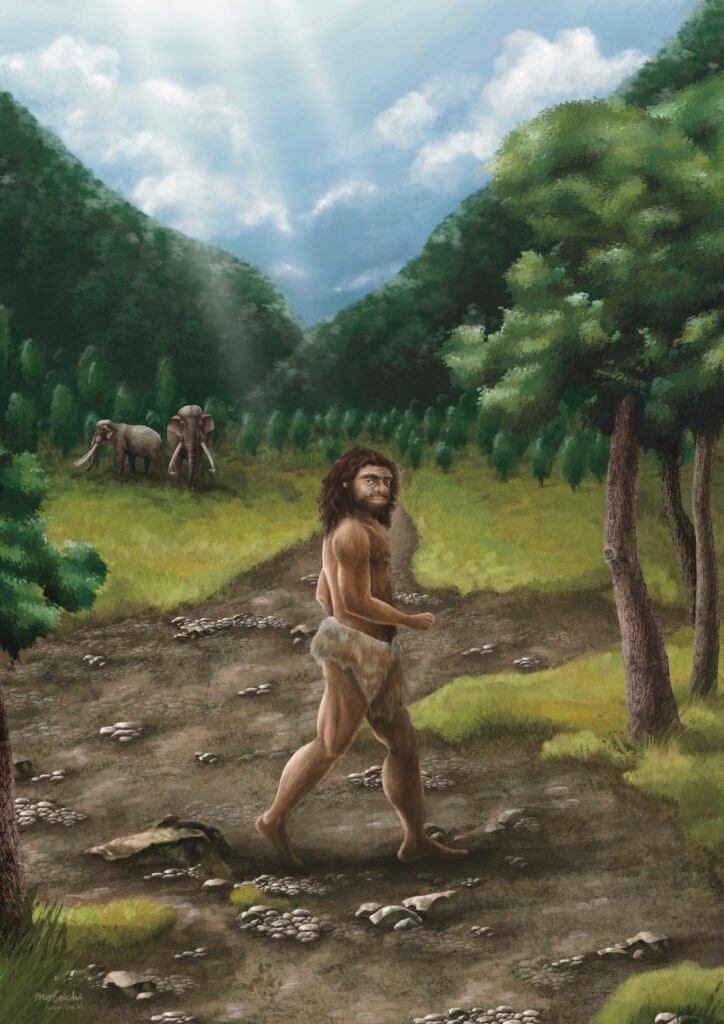

To understand why this find matters, we need to step back some 40,000 to 300,000 years. During this window of time, at least three groups of humans shared Eurasia: Homo sapiens (us), Neanderthals, and Denisovans. While Neanderthals have captured the public imagination with their robust skeletons and close genetic ties to modern Europeans, Denisovans have remained shadowy, largely invisible figures.

In fact, before 2010, no one even knew they existed.

The first clue came from a fragment of a finger bone, discovered in Siberia’s Denisova Cave. DNA extracted from this tiny bone revealed a previously unknown group of archaic humans—distinct from both Neanderthals and modern humans. Since then, only a handful of Denisovan remains have been found: a few teeth, part of a skull, and a partial jawbone high in the Tibetan Plateau. These fossils suggested Denisovans were widespread but left a frustratingly light footprint in the archaeological record.

Which is why the Taiwan jawbone is such a big deal.

A New Dot on the Denisovan Map

“This find really pushes the boundaries of what we know about Denisovan distribution,” said Takumi Tsutaya, co-author of the study and a researcher at Japan’s Graduate University for Advanced Studies. Until now, all confirmed Denisovan fossils were discovered in cold, mountainous regions—Siberia and Tibet. The jawbone from Taiwan, in contrast, hints that these ancient humans also traversed the warmer, subtropical zones of East Asia.

That’s a geographic leap of over 2,000 kilometers.

“This discovery not only expands the Denisovan map but also raises tantalizing questions about their migration patterns,” Tsutaya noted. “How far did they travel? Did they cross water? Did they have maritime skills? We just don’t know—yet.”

Cracking the Code Without DNA

One of the major challenges in studying ancient fossils is extracting DNA, the gold standard of evolutionary analysis. Unfortunately, the jawbone’s condition—having spent centuries submerged—made DNA recovery impossible. But scientists found another way: protein sequencing.

By analyzing ancient proteins preserved in the fossil’s dentin (a dense tissue beneath the tooth enamel), researchers in Taiwan, Japan, and Denmark were able to reconstruct part of its molecular profile. This biochemical fingerprint revealed similarities with proteins found in confirmed Denisovan specimens from Siberia.

Though not as precise as genetic sequencing, this approach represents a powerful tool in paleoanthropology, especially when DNA is degraded or absent.

Rick Potts, director of the Smithsonian’s Human Origins Program, praised the research as a “fantastic job of recovering some proteins.” However, he cautioned that conclusions should be tentative: “It’s a very promising lead, but more evidence is needed before we can definitively call it Denisovan.”

Shadows of Ancestors in Modern DNA

Though Denisovans have left behind scant fossils, they’ve left a much larger mark in a surprising place: inside us.

Through interbreeding with both Neanderthals and early Homo sapiens, Denisovans passed on segments of their DNA to modern humans. Today, Denisovan genes can be found in the genomes of Indigenous peoples in parts of Southeast Asia, Melanesia, and even among some East Asians. These genetic legacies include adaptations to high-altitude environments—such as those seen in Tibetan populations—hinting at Denisovans’ ability to survive in extreme conditions.

“We can identify Neanderthal elements and Denisovan elements in the DNA of living people,” Tsutaya explained. “It’s proof that these weren’t isolated populations. They interacted. They mingled. They left traces in us.”

The Taiwan jawbone may, therefore, represent not only a lost individual but a long-silent witness to the dynamic and complex intermingling of ancient human species.

Redrawing the Evolutionary Map

Every new Denisovan find redraws our mental map of ancient human history. Before 2010, Denisovans were unknown. Before 2019, they weren’t believed to have reached the Tibetan Plateau. And now, with this new discovery, they’re part of the prehistory of Taiwan—potentially opening the door to future finds across Southeast Asia.

Some researchers suspect Denisovans may have reached Indonesia or even Australia, given their genetic footprint among Indigenous peoples there. If so, where are their bones? Have they eroded? Are they still buried beneath jungles, or sunk beneath the sea, waiting to be found?

This tantalizing possibility gives renewed urgency to fieldwork in the region. Fossils like the Taiwan jawbone suggest Denisovans were much more widespread—and adaptable—than previously thought.

Mysteries Beneath the Surface

There’s an added twist to the story: the fossil wasn’t even discovered on land. It came from the seafloor—a region that was dry land during the Pleistocene, when sea levels were lower due to glacial cycles. This ancient “land bridge” would have connected Taiwan to the mainland, serving as a potential migration route for early humans, animals, and now, we believe, Denisovans.

The fossil’s preservation, encrusted with ancient marine invertebrates, suggests it lay undisturbed on the ocean bed for tens of thousands of years—an accidental time capsule awaiting rediscovery.

It raises a fascinating question: how many more ancient human remains lie beneath our oceans, displaced by rising seas, waiting to be dredged up or revealed by future technology?

A New Chapter in Human History

This is more than just the story of a jawbone. It’s the unfolding saga of our species—and the others we shared the planet with. Denisovans, long thought to be confined to the icy caves of Siberia and the Himalayas, now appear to have roamed further than we ever imagined, reaching the lush corridors of East Asia’s coastal lowlands.

With each new discovery, we get a little closer to understanding these ancient cousins. Who were they? What did they look like? How did they live—and die? The Taiwan jawbone doesn’t answer all these questions, but it adds another precious fragment to the puzzle.

And as our tools for extracting data from ancient materials continue to evolve—whether through protein analysis, sediment DNA, or underwater archaeology—our vision of the distant past grows sharper, richer, and more complex.

For now, the Denisovans remain part ghost, part reality: a people we barely know, yet whose legacy may be written in our bones.

Reference: Takumi Tsutaya et al, A male Denisovan mandible from Pleistocene Taiwan, Science (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.ads3888. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.ads3888