For more than a century, the armored titans known as ankylosaurs have fascinated paleontologists and dino-enthusiasts alike with their tank-like bodies, weaponized tails, and secretive evolutionary past. Now, in a stunning twist of scientific fortune, paleontologists have uncovered something unprecedented hidden beneath the remote terrain of the Canadian Rockies: the very first fossilized footprints of tail-club-wielding ankylosaurs ever recorded. Not only do these tracks rewrite the narrative of North American dinosaur evolution, but they also introduce a brand-new member to the dinosaur family tree—Ruopodosaurus clava, “the tumbled-down lizard with a club.”

Footprints Frozen in Time

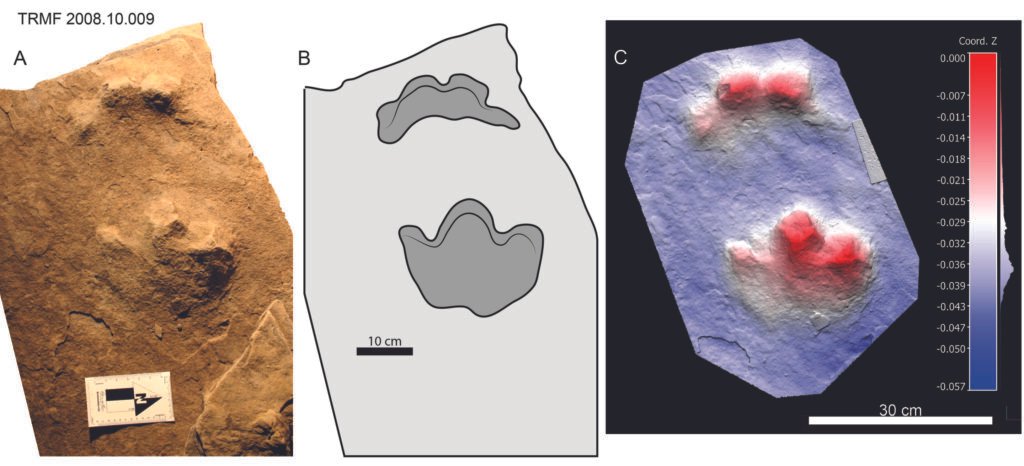

It began in the mountainous wilds of British Columbia and Alberta, where steep cliffs and prehistoric sediments cloak secrets from the Cretaceous period. Tucked among these rugged formations near Tumbler Ridge, BC, and in northwestern Alberta, researchers uncovered something extraordinary: a collection of three-toed dinosaur footprints, fossilized in stone, dating back 100 million years to the mid-Cretaceous period.

For years, paleontologists were familiar with ankylosaur tracks across North America—broad, four-toed impressions attributed to a track type called Tetrapodosaurus borealis. These were made by nodosaurid ankylosaurs, tail-club-less cousins of the more heavily armed ankylosaurids. So when these three-toed tracks were found, their strange shape immediately raised questions.

Could these tracks represent an entirely different kind of dinosaur?

Three Toes and a Tail Club

The key to unlocking the mystery lay in the toes—and the tail.

Ankylosaurs are divided into two main evolutionary branches. Nodosaurids have four toes on each hind foot and lack the signature bony tail club. Ankylosaurids, on the other hand, are distinguished by having three toes and a formidable weapon at the end of their tail—a massive, bony club capable of delivering devastating blows. These three-toed prints bore a striking resemblance to what would be expected from the latter group.

After careful analysis, a team of scientists led by Dr. Victoria Arbour, curator of paleontology at the Royal BC Museum and one of the world’s foremost experts on ankylosaurs, confirmed the impossible: these tracks were indeed made by an ankylosaurid dinosaur—the first such tracks ever identified.

To honor both the discovery’s unique features and its mountainous birthplace, the team named the new species Ruopodosaurus clava. The name translates roughly to “the tumbled-down lizard with a club,” referencing both the rugged, sloping terrain where the tracks were found and the animal’s distinctive weaponized anatomy.

The Discovery Team and Their Mission

The discovery was the result of years of meticulous research, local exploration, and scientific collaboration. Dr. Victoria Arbour’s fascination with armored dinosaurs stretches back decades. Her work has taken her across continents, uncovering fossilized skeletons and unraveling the deep-time evolution of these Cretaceous juggernauts. Yet even for Arbour, this find felt different.

“Ankylosaurs are my favorite group of dinosaurs to work on,” Arbour shared. “So being able to identify new examples of these dinosaurs in British Columbia is really exciting for me.”

Her enthusiasm is echoed by Dr. Charles Helm, scientific advisor at the Tumbler Ridge Museum, who had been documenting these enigmatic three-toed trackways for years. Helm first noticed them while exploring the ancient sediment layers around Tumbler Ridge and suspected they might represent something new.

In 2023, Helm invited Arbour to examine the mysterious tracks in person. What followed was a detailed comparative study that brought in other experts, including Eamon Drysdale, curator at the Tumbler Ridge Museum; Roy Rule, geoscientist at the Tumbler Ridge UNESCO Global Geopark; and the late Martin Lockley, a pioneer in dinosaur track research from the University of Colorado.

Together, they pieced together a clearer picture of a creature once lost to time.

A Tail-Clubbed Titan of the Cretaceous

Though no skeletal remains of Ruopodosaurus clava have been found—yet—the tracks tell us a surprising amount about the creature that left them. The dinosaur would have measured around 5 to 6 meters (16 to 20 feet) in length. Like other ankylosaurids, it was heavily armored with osteoderms—bony plates embedded in its skin—and likely had spikes protruding along its sides for extra protection.

Its most striking feature, however, was the stiff, bony club at the end of its tail. Much like a medieval mace, this natural weapon was capable of swinging with enough force to shatter bone or deter predators like tyrannosaurs. Evolution shaped ankylosaurid tails into rigid rods supported by interlocking vertebrae, with the club forming from two enlarged tail bones fused together and encased in layers of bone.

The three-toed footprints left behind are broad, heavy, and well-preserved, indicating the animal was a ground-hugging quadruped with powerful limbs—traits synonymous with ankylosaurids.

The Significance of the Discovery

What makes this discovery especially groundbreaking is not just that it introduces a new species, but that it fills a long-standing gap in the fossil record.

Skeletal remains of ankylosaurid dinosaurs have been notably absent in North America during the mid-Cretaceous period—from roughly 100 to 84 million years ago. This lack of fossil evidence led some scientists to hypothesize that ankylosaurids may have gone extinct in the region during that time, only to reappear millions of years later.

The Ruopodosaurus tracks disrupt this narrative.

“These footprints show that tail-clubbed ankylosaurs were alive and well in North America during this gap in the skeletal fossil record,” Arbour explained. The fossilized tracks serve as hard evidence that ankylosaurids didn’t disappear—they simply left fewer bones behind, or their remains have yet to be found.

Moreover, the discovery also confirms that both major ankylosaur subgroups—nodosaurids and ankylosaurids—coexisted in the same region during the mid-Cretaceous, offering a more nuanced view of the ecosystem dynamics during that time.

Tumbler Ridge: A Hotspot of Prehistoric Life

Tumbler Ridge, once a coal mining town, has quietly evolved into a paleontological treasure trove. Since the year 2000, when two local boys stumbled across the first known ankylosaur trackway near the area, Tumbler Ridge has gained increasing scientific prominence. It now houses the Tumbler Ridge Museum and is part of the Tumbler Ridge UNESCO Global Geopark, both devoted to protecting and studying the region’s rich fossil heritage.

Dr. Helm remarked, “Ever since two young boys discovered an ankylosaur trackway close to Tumbler Ridge in the year 2000, ankylosaurs and Tumbler Ridge have been synonymous. It is really exciting to now know through this research that there are two types of ankylosaurs that called this region home.”

The area’s significance continues to grow with every new find, further underscoring how much of the prehistoric world is still buried beneath our feet.

“This study also highlights how important the Peace Region of northeastern BC is for understanding the evolution of dinosaurs in North America,” said Arbour. “There’s still lots more to be discovered.”

A Glimpse into an Ancient World

Each fossil track is more than a footprint—it’s a snapshot of life frozen in stone. The Ruopodosaurus clava discovery is a testament to the stories that the earth can tell, even without bones. It paints a vivid picture of a creature armored like a tank, walking with deliberate force across the soft mud of a Cretaceous floodplain, leaving behind impressions that would endure for millions of years.

Its presence in what is now a cold, mountainous wilderness speaks of a time when British Columbia was warm, teeming with plant life, and roamed by giants.

This discovery also reignites curiosity about what else remains undiscovered. Could there be full skeletons waiting to be found? What other species lived alongside Ruopodosaurus clava? How did these two ankylosaur types interact—were they rivals, or did they occupy different ecological niches?

The fossilized tracks of Ruopodosaurus don’t answer all these questions—but they crack open the door to a realm of possibilities.

The Legacy of Ruopodosaurus

In paleontology, every new discovery is a key, and sometimes that key unlocks entire chapters of prehistory. The footprints of Ruopodosaurus clava don’t just belong to a single dinosaur—they represent a bridge between what we know and what we’ve yet to learn. They show us that even in the apparent silence of stone, there is a record—a living memory of creatures that ruled the Earth long before us.

And in the echo of each footprint, we find not just evidence of an armored beast with a mighty tail, but a reminder of how much of our planet’s history is still waiting to be written.

Reference: A new thyreophoran ichnotaxon from British Columbia, Canada confirms the presence of ankylosaurid dinosaurs in the mid Cretaceous of North America, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology (2025). DOI: 10.1080/02724634.2025.2451319